The Dayton Pesthouse Murders

Story: One of the most perplexing unsolved cases in Iowa's history took place over 100 years ago in the town of Dayton. The facts of the case are simple yet intriguing-three men, one women, and one child were savagely slashed to death in their beds over a three month period. The surprising, if not tragic, dimension of the case is that all of the victims were dying of smallpox in the county pesthouse. Despite Sheriff Joshua Petersen's diligent efforts, no arrests, no suspects, and no clues to the identity of the perpetrator was ever discovered.

Recently, the great grand daughter of one of the principles in the century old Dayton Pesthouse Murders told me her discovery of secret journals compiled by her forefather. I soon read with quaking hands the answer to this grisly riddle so many have sought for so long. An answer so disturbing, that I promised the sobbing perpetrator's descendant never to reveal her name and in so doing, protect her and her family's lives.

The house is filthy and decaying. The roof leaks and the walls are black with soot. There is inadequate ventilation, both floors limited to only four windows which provide feeble light during the day. The nearby well has been filled with refuse, its water is most certainly unpotable. Floors are dirty, with large solid encrustations of various sputum and other wastes. The old army cots are soiled and louse ridden and I counted no less than one dozen rats skulking along the walls. Some barns are more fit for the convalescing sick than this "Hospital"!

Dr. Cotton's 1901 visit to the Dayton Pesthouse

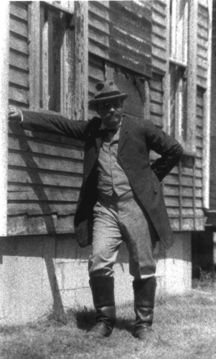

Gruber arrived mysteriously from the Oley Valley of southeastern Pennsylvania with no further explanation than that he was called forth to help. By whom, he never imparted to any living soul. This hale and robust middle aged "Dutchman" bore a distinctive pale white scar on his left cheek. Ham fisted and big as an oak, he brought with him a leather bag of bundled herbs, bottled tinctures, and a well-thumbed volume of Der Lang Verbogen Freund by John G. Hohman. Intelligent and well read, Gruber claimed he had once cured a boy with tuberculosis with sassafras tea prepared with a sliver of tubercular lung tissue from a cow. In his statement to Sheriff Petersen, Dr. Cotton initially felt inclined to eject him from the premises, but he needed the help and Gruber's remedies showed curative effects.

On the morning of September 23, 1879, the first murder victim was discovered. In an isolated corner of the second story of the house, Dr. Cotton found the partially eviscerated body of Brody Evans. Evans had been doing poorly and was expected to die soon. As a duly appointed Medical Officer of the County, Dr. Cotton recorded the cause of death as "...multiple cutting wounds to the throat and chest and further mutilations made with a large knife."

Petersen naturally suspected Gruber. The herbalist was known to carry a large Bowie knife and his compassion for the patients was such that Petersen thought he might kill them than let them suffer. But Gruber proved he had been ten miles away at the Bechtel farm the entire night helping Mrs. Bechtel deliver twins and had only returned that morning. Patients claimed they neither heard nor saw anything unusual in the night; albeit a night riddled with the piercing cries of fevered delirium.

Three weeks passed. Dr. Cotton and Gruber were having some success in helping most of their patients fight off the disease. News of this reached Des Moines, attracting dozens of tramping poor to the house. On Sunday, October 5, 12 year old Emily Faqua was found dead. She had arrived two days before from Ames under the devoted care of her mother, Susana. Already delirious and covered with large sores, she was immediately given a bed in the second story of the house. Just before dawn, Susana had left her daughter's side to fetch some cold water only to return and find Emily awash in her own blood; her throat slashed and her belly gashed open.

Petersen questioned other patients and learned little. In his notes, he wrote, "Having viewed the girl's corpse with Dr. Cotton, we both feel the act was done by the same man. But, as all patients possibly connected with the previous incident have left the house or passed on, I am loath to assume the murderer was indeed a fellow inmate. As Mr. Gruber has once again provided both an excuse and witnesses for his whereabouts, I am once again at wits end in this tragic case."

Two interesting coincidences quickly followed this second killing. First, nearly all of the 41 cases of smallpox were cured within ten days. And second, was that Gruber unexpectedly left the pesthouse.

In mid-October, the smallpox scourge swept scythe-like through Dayton. Within days, nearly 80 patients were crowded into the cramped house; few had beds. On the evening of October 31, three gravely sick men, allegedly railroad workers, were brought in. They were taken up and placed in one tiny, cramped space in the back of the house used for storage. Early next morning, Dr. Cotton made his rounds and discovered all three men had been barbarously killed.

Petersen's investigation once more faltered. With little recourse, he obtained a warrant for Gruber's arrest but reported to the Town Council that he did not believe the man involved in the murders. In the end, Gruber vanished without trace; the murders ended, and the smallpox outbreak subsided by Christmas that year.

That spring, the Quarantine Commission disbanded, and Dr. Cotton, so instrumental in ending the outbreak, quietly moved to St. Louis. He set up an exclusive practice among that city's gentry using methods he developed in Story County. In 1900, he joined the faculty of Washington University and was known as a distinguished epidemiologist and scholar until his death in 1941.

For nearly fifty years, it was assumed all of his papers and other writings had been archived by the university until his great grand daughter discovered a secret panel while remodeling the family home. Inside this cubby, she discovered a pair of mildewed journals written in Dr. Cotton's own hand:

"November 1, 1879: Last night, I escaped with my life after a struggle so horrible and bloody acts so vile that I am filled with self loathing to the point that I might gladly hang for what I have done. But the knowledge I have gained cautions me that I can yet cure the diseased. Perhaps it is my own ambition that makes me play the coward. And yet, I must confess myself some how.

It was ambition that pricked me to this desperate state. When poor Gruber arrived with his silly book of simple backwoods cures, I allowed him to stay as a kindness to my patients. I had no idea he was so gifted as a healer, nor so well versed in medical theory. I believed I grasped the nature of his primitive cures against the contagion and allowed him to use a peculiar salve of his own devising on one poor woman. This ointment he explained was composed of willow ground and mixed with vinegar and the juice of a large yellow flower. He found these flowers growing in a bed of white clay near a stream about a mile distant. I believe them a subspecies of Chelidonium majus , and are much larger with blooms nearly two inches across. When applied, the woman's sores shrank within a few hours, fever lessened, and she rested comfortably. I could offer no such similar remedy.

Jealousy and ambition bewitched me. Short of preventive vaccination, there is no cure for those who have smallpox. They conquer it or are conquered by it and so perish. I developed a theory following Hahneman's homeopathic philosophy that I believed could readily cure those afflicted with smallpox. I was so sure, so certain, I imagined myself above the laws of Man and God. I assured myself that my endeavors were solely for the noble purpose of benefiting humankind. I drew my old bayonet through my first victim's throat confident he was dying to save others. I removed the organ I required in darkness and committed a few swift slashes to conceal my purpose.

I shortly produced an extract of the organ and commingled it with some juice of the large Chelidonium majus flowers. I then administered it orally to six patients, all with well established infections. Gruber questioned me about what it was. I said nothing, deciding to let him wonder at my genius when all would soon rise from their sickbeds. But it was not to be. On October 5, five of the six perished after a night of screaming agony, perhaps poisoned by my mixture. But this failed to deter my ambition. I decided to separate the red and white pulpy masses. I would try again using only the white.

Emily died as I approached her---I had no hand in that poor child's demise. But time was against me and her spleen had to be removed and processed before any decomposition set in. I reenacted the murder as before, carrying out similar hasty depredations on the corpse for concealment. I rounded a corner just in time to cringe at Susana's shriek and wail. I wanted very much to comfort that dear mother, but her daughter's blood was still warm and sticky on my hands. I fled.

On October 15, my efforts triumphed. The secret had been the white pulpy masses. Patients rose from their beds within 3 to 4 hours of drinking the mixture. Gruber soon told me he was leaving to help the sick at a railroad work camp some twenty miles away. I said I would miss him despite his mediaeval potions. He laughed loudly at that. I will always treasure the image of that white scar on his cheek suddenly wrinkling and flushing with his mirth. He asked me what spirits I conjured to cure our patients. How could I tell him the demon I bargained with was my own ambition?

The house was soon filled with more sick as the scourge rushed through the county. We were overwhelmed. I soon used up the last of my mixture saving those not likely to survive. Desperate, I laid plans to prepare a new batch when the opportunity arose. The night of Halloween, word came that three badly ill railroad workers were brought in and placed upstairs in the back storage room as no where else was available. I waited late until moonset and ventured off to the pesthouse so that one of these poor fellows would save his friends.

Entering the house, I proceeded to where the railroad workers were sequestered. I selected the man closest to me and as I straddled his chest to deliver a dispatching cut, he shrieked the most terrible rasping and raw cry; one like a stone grinding across a broken bottle. His two burly friends lurched to their feet. As I drew my old bayonet cleanly across the unwilling donor's throat, I felt their scabby hands about my neck and shoulders. They flung me to the floor, only to lie atop me drained by their exertions. I couldn't move as my legs were still upon the bed and one arm was bent behind my back. They attempted to call out but merely coughed, the larger of the two--a giant of a man--gagged and retched on my chest. He clamped a muscular hand across my throat and squeezed limply, while his other feebly wrestled with my knife hand. It was a languishing struggle, desperately played out in the perfect stillness of a grave. His breath reeked of puke, I nearly swooned. With a stupendous effort, I twisted and freed my arm from behind my back. I wrenched the man's head aside and drove my blade deeply into his throat. He gurgled and rolled away.

I hardly recall what followed. I found myself in the midst of the room, drenched in blood, enthralled by rage and fear like a vicious beast. I lit a candle and upon the flame's sputtering to life, beheld the ghastly trio; their heads sorrowfully slashed and nearly hacked off, their innards unstrung all over the floor.

A noise came from below. It may have been an inmate rustling, but it sounded like an eruption. In the dim light, I sprang to action and extracted the white pulpy masses from each man's spleen. More blood flowed. Again, I heard the noise. Then it occurred to me: blood was seeping through the floorboards!

I looked everywhere for something to wipe myself with, but blood had spattered everything. At last, I glimpsed a rough cleaning rag hanging from the side of a bucket near the door. Hastily, I wiped away as much blood as I could and fled stealthily outside into the cold star lit night, clasping the jar that held the white masses. I leapt to my horse and galloped home in a few minutes. There, I burned my crimson stained clothes in the grate.

On the morrow, I rose and returned for my morning rounds. Despite the telltale stain of blood on the ceiling above which none noticed, all was normal. Likewise, I continued upstairs in my customary way, entering the back room last. It was then upon revisiting the horrors I'd inflicted the night before that I raised the alarm.

Only later, after I filled out the death certificates as Identity Unknown, were the three corpses removed from the house into the daylight. At once I staggered; struck through by a bolt of blue horror. Gleaming in sunlight, on a face wrecked by my own hand was Gruber's pale scarred cheek."

Back to this Issue Contents